A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

Before the pandemic, Elizabeth Santamour dreaded seeing a certain stack of envelopes once a month in her mailbox. A third-grade teacher in Scurlock, North Carolina, she was tasked with handing out past-due cafeteria bills to her students.

“The kids knew what they were taking home to their parents and the reaction they were going to get. They knew,” Santamour said. “I had kids who left them in their book bags for days. When I handed them to some kids, they’d get upset. Others would refuse breakfast or lunch because of the expense they knew they were accruing.”

Prior to the pandemic, some schools that were determined to manage school meal debt had resorted to tactics that embarrassed kids, such as stamping their hands to remind parents of unpaid bills and substituting cold cheese sandwiches for hot meals.

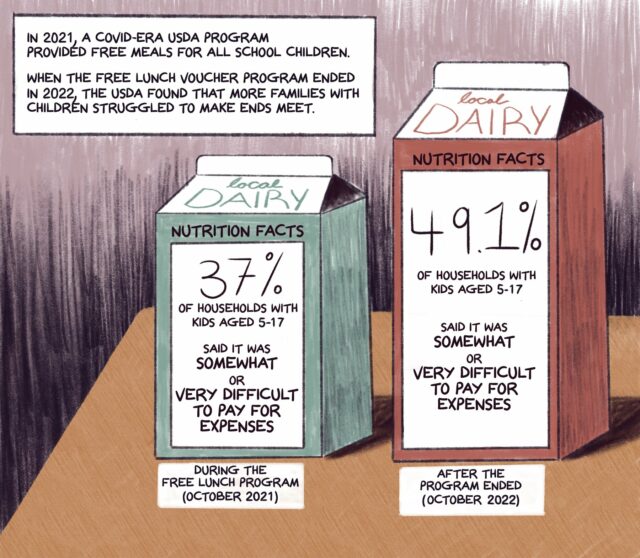

Students and teachers nationwide had a two-year break from this pressure when federal pandemic waivers allowed free meals for all. That was followed by a transition year of higher per-meal reimbursements funded by the Keep Kids Fed Act. But those expired in July. Now the burden of school meal debt begins again, at a time when experts are declaring a kids’ mental health crisis as a broad array of stressors, from gun violence to climate disasters, roil their world.

The Education Data Initiative pegs the annual national public school meal debt at $262 million. What’s more, after free school meals for all ended, 67 percent of schools surveyed by the School Nutrition Association (SNA) reported an increase in stigma for low-income students who often depend on those meals as a key source of nutrition.

“Schools, families, and states really did not want to go back to having the complicated school nutrition operations where some kids have access to free meals and other kids do not, and they have to struggle with unpaid debt,” said Crystal FitzSimons, the director of school and out-of-school time programs at the Research and Action Center (FRAC).

And in a small handful of states, they haven’t gone back: Lawmakers in California, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Vermont have made universally free school meals permanent. But in the rest of the country, the return to paid school meals has also brought back a host of complications.

Prior to the pandemic, some schools had resorted to tactics that embarrassed kids, such as stamping their hands to remind parents of unpaid bills and substituting cold cheese sandwiches for hot meals. Sometimes meals were thrown out in front of the children. And while experts say that fewer districts have resumed these practices—often dubbed “lunch shaming”—they haven’t gone away entirely either.

A Vicious Cycle of Debt and Stigma

In general, schools have financed breakfast and lunch programs primarily through per-meal reimbursements from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). To receive those reimbursements, which vary based on family income, schools must provide meals that meet certain nutritional standards.

Children in households with incomes at or up to 130 percent of the federal poverty level can receive free meals; those whose households have incomes between 130 and 185 percent are charged 30 cents for breakfast and 40 cents for lunch.

“We certainly hear from school districts with large immigrant communities that there are lots of families who are uncomfortable filling out that application, but definitely need assistance.”

School meal programs are expected to be self-sustaining, according to the SNA. Districts attempt to cover expenses with the federal reimbursements, as well as cafeteria sales from both full- and reduced-price meals. But that’s been increasingly difficult as food and labor costs have risen. Plus, “many of the families who are eligible for reduced-price meals still struggle with that copay,” noted Diane Pratt-Heavner, a spokesperson for the SNA.

And there’s another rub. Families must apply for federally subsidized meals if they are not automatically eligible through programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). “These applications for free meal service have always been a barrier for eligible families,” Pratt-Heavner added. For example, income information and the last four digits of a social security number are required. People who don’t have a social security number must check a box declaring that fact.

“We certainly hear from school districts with large immigrant communities that there are lots of families who are uncomfortable filling out that application, but definitely need assistance,” said Pratt-Heavner. And schools need the reimbursements to help cover the cost of the meals.

The application process can be a barrier for families in several ways. Juliana Cohen, an associate professor in the department of nutrition and public health at Merrimack College and an adjunct associate professor in the department of nutrition at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, said that completing the form is effectively saying, “I can’t afford to feed my child.”

“Oftentimes these forms are on a brightly colored piece of paper. They say ‘Free School Lunch Form.’ And a parent has to give it to their child to bring back to the school to hand to their teacher. So, many parents are actually reluctant to even fill out the form. Additionally, there can be stigma for the child if they feel like they’re different.”

Since the pandemic reprieve from the application system, another challenge is that many families are now confused about what’s required. If they don’t apply, debt builds.

Laura Milliken, executive director of New Hampshire Hunger Solutions, believes that confusion is one of the drivers of the fast-growing meal debt among schools in her state. “As a result, we are hearing from schools that many of them have amassed quite high school meal debt from kids who eat and then families don’t pay.”

A Flurry of State Legislative Activity and Public Sentiment

There was a wave of media coverage related to lunch shaming prior to the pandemic. And it appears to have had an impact.

“People have a very visceral reaction to those stories, they get a lot of traction, and kids often have phones in school,” which allowed them to document and share the stories themselves, said FitzSimons. After the spate of publicity, experts say the overt actions diminished.

At least 20 states also have taken action against lunch shaming with specific legislation, according to FRAC. North Dakota is among the most recent, with a law signed in April that prohibits public identification or stigmatization of students whose parents have outstanding meal debt.

But some anti-shaming bills have failed. In January, for example, a New Hampshire state representative introduced such a bill, and it was killed the following month. Another effort by legislators there—a bill to raise the income threshold for reduced price lunches from 185 percent to 300 percent of the federal poverty level—made it as far as a Senate committee, which recommended delaying a decision until next year.